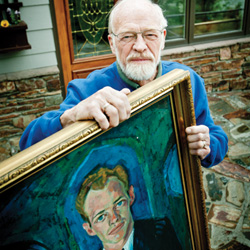

Pastors often keep things in their studies that remind them of God’s goodness and grace. But Eugene Peterson kept something else in his office: a painting that terrified him. He was a seminary student in New York City and had been hired as a pastor of a small Presbyterian congregation made up of a lot of artists. One painter in the church was named Willi Ossa, who also served as the part-time church janitor.

Here is an excerpt from Peterson’s marvelous autobiography called The Pastor:

Willi had a severely negative opinion of the church. “Severely negative” is an understatement. It was outraged hostility. He had lived through the war and personally experienced at close quarters the capitulation of the German church to Hitler and the Nazis. His pastor had become a fervent Nazi. … He couldn’t understand why I would have anything to do with church. He warned me of the evil and corrupting influence it would have on me. He told me that churches, all churches, reduced pastors to functionaries in a bureaucracy where labels took the place of faces and rules trumped relationships. He liked me. He didn’t want his friend destroyed.

And then he began painting my portrait. He said he wanted to work in a form that was new to him. But he would never let me see what he was painting.

One afternoon Mary [his wife] came into the room, looked at the nearly finished portrait, and exclaimed “Krank! Krank!” I knew just enough German to hear “Sick! Sick!” In the rapid exchange of sharp words between them, I caught Willi’s “Nicht krank, aber keine Gnade” — “He’s not sick now, but that’s the way he will look when the compassion is gone, when the mercy gets squeezed out of him.”

A couple weeks later the portrait was complete and he let me see it. He had painted me in a black pulpit robe, seated with a red Bible on my lap, my hands folded over it. The face was gaunt and grim, the eyes flat and without expression. I asked him about Mary’s Krank. He said that she was upset because he had painted me as a sick man. “And what did you answer her?” He said, “I told her that I was painting you as you would look in 20 years if you insisted on being a pastor.” And then, “Eugene, the church is an evil place. No matter how good you are and how good your intentions, the church will suck the soul out of you. I’m your friend. Please, don’t be a pastor.”

His prophetic portrait entered my imagination and has never faded out. But I didn’t follow his counsel. Eventually I did become a pastor. But I have also kept that portrait in a closet in my study for 55 years as a warning: Willi’s prophecy of the desolation that he was convinced the church would visit on me if I became a pastor.

I still pull it out occasionally and look at those vacant eyes, flat and empty. The face gaunt and unhealthy. Willi’s artistic imagination created a portrait that was far more vivid than any verbal warning. The artist has the eyes to connect the visible and the invisible and the skill to show complete what we in our inattentive distraction see only in bits and pieces.

I don’t have a haunting portrait in my office, but I do have something similar: a little caricature that warns me in its own way. Not a painting of a dilapidated Tyler, but of a character from The Simpsons. On my shelf stands an action figure of Rev. Timothy Lovejoy, pastor of The First Church of Springfield. While Rev. Lovejoy is a minister, he can’t stand his church. He would rather work on his model trains than his congregation, he’s cynical about people changing, and he treats ministry like a competition. In short, he’s everything I aspire not to be.

Thankfully, you don’t make me feel like a gaunt version of myself nor do you make me feel like a jaded Simpsons character. But I still keep Rev. Lovejoy on my shelf as a constant reminder to remain diligently, fervently committed to hope, to kindness, to compassion, to optimism, and to grace.

Sometimes we need that. In life we not only need exemplars who inspire us to be our best selves, but we also need foils we can point to and say, “Please, Lord, do not let me become that.” We can have grace for those people and recognize we are as flawed as they are. But that grace does not mean that we have to embody their character or way of being.

But our ultimate model is not a warning figure—it is Jesus himself. In Christ we don’t just see what to avoid, we see what to become: heaven meeting earth, the kingdom incarnate, God’s love moving into the neighborhood.

Tyler Tankersley